Published on April 21st, 2020

Written by Toussaint Nothias

In 2016, Facebook’s grand project to ‘connect the unconnected’ was banned in India after a year-long national debate led by net neutrality activists. Globally, however, the project kept expanding, particularly across Africa: by the summer of 2019, at least 32 African nations had offered the service at one point in the last five years. What made this quiet expansion possible post the India debacle? And what does it mean for the future of civil society resistance to tech corporations?

As part of their efforts to increase their global reach, US tech corporations have invested in a range of connectivity projects across the Global South. One of the most notorious ones is Facebook’s Free Basics initiative. Free Basics is both an application and website that provides free of data charges access to a variety of basic services like news, weather and health information, job ads, and of course, Facebook. Designed to work on both feature and smartphones and in contexts of limited bandwidth, this walled-garden model is reminiscent of a 1990s AOL web portal. While Facebook initially presented the project as philanthropy targeting unconnected rural communities, it follows a gateway drug commercial model: this sample of connectivity will spur greater data consumption, and in the process grow Facebook’s user base while cementing the corporation’s position as the gateway to the Internet for mobile users across the Global South. A confidential internal document from April 2015 (figure 1) shows how Facebook kept track of the project, including a list of 25 priority countries and government support.

Figure 1 – Facebook’s internal Free Basics (FBS) tracking document, April 2015. This document is part of a trove of nearly 4,000 pages of internal emails, reports, and other documents submitted as part of a lawsuit in California state court between Facebook and Six4three LLC, a former Facebook app developer. These documents were leaked to reporter Duncan Campbell and made publicly available by NBC News.

As the initiative was being rolled out in India in 2015, a group of local activists forcefully opposed it (see Prasad, 2018 for an informed analysis of this campaign and its context). Their main criticism was that Facebook acted as a gatekeeper of the internet by pre-selecting services available on the app without transparency and with detrimental effects on smaller services and local start-ups. In a nutshell, they decried Free Basics and other zero-rating offers as a violation of net neutrality, i.e., the principle that internet service providers should treat all internet traffic equally. Throughout 2015, a highly publicized national debate over net neutrality unfolded. It concluded in early 2016 with the Indian regulator banning zero-rating, including Free Basics.

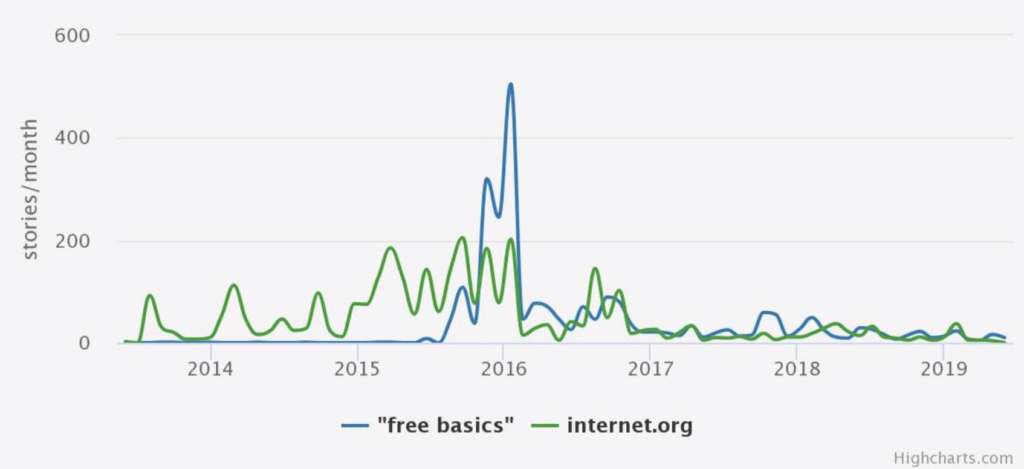

This ban was widely perceived as a massive victory for digital rights activists in India and beyond. For Facebook, it was the first major global political scandal before the fall-out of the 2016 US elections and the Cambridge Analytica scandal. To many observers, then, the pushback in India seemed to signal the end of Free Basics. Indeed, in my research, I find that there is a peak of global news coverage in 2015 related to India, and then it dramatically decreases, as if the project had stopped (Figure 2). But this is highly misleading.

Figure 2 – Number of news stories about “Free Basics” and “Internet.org” across 1500 Global English Language sources, June 2013 – July 2019 (Source: Media Cloud)

In fact, Facebook moved forward with the project around the world. In early 2016, Free Basics was reportedly available in 30 countries. By the end of 2016, Facebook earning calls transcript noted that Free Basics – along with other Facebook connectivity projects- had contributed to bringing online 40 million people. By the end of 2018, the number was up to 100 million people. By 2019, the number of reported countries had increased to 65 countries, including 30 in Africa.

One should be cautious here because these numbers are provided by Facebook. There is a need for independent data, but this is a challenge because access to Free Basics is geographically restricted. You have to be in the country, using a sim card from a partnering telecom operator to access the service. In my research, I used a VPN service with locations in all countries on the continent. This did not allow me to access Free Basics per se; however, each country has a different landing page for 0.freebasics.com which states if the service is available, and in partnership with which telcos.

Here is what I found (Figure 3). In July 2019, Free Basics was live in 28 African nations and no longer available in 3. There were also discrepancies between what Facebook reports as the current countries and telco partners, and what I found. My full analysis (Nothias, 2020) discusses this in more detail, as well as countries where the project was announced but not launched and Egypt where it was banned. Overall, 32 African countries offered Free Basics at some point since 2014. I am always worried about generalizing about Africa, but this is quite a continental expansion.

Figure 3 – Overview of Free Basics in Africa (Data about availability of the service as of July 2019 obtained independently through VPN proxy).

Why didn’t we see more pushback across these countries like the one in India? Or why wasn’t there more of a spillover effect from the India debate to these other parts of the world? In my paper, I argue that it’s because of the combination of two key interrelated phenomena: 1) Facebook’s evolving strategy, particularly its growing engagement with civil society organizations; and 2) the focus of digital rights activists across the continent on other issues including internet shutdowns, government censorship, and the lack of data privacy frameworks.

In light of the India debacle, Facebook increased its engagement with local civil society groups. In partnership with a South African NGO – the Praekelt Foundation – it launched an incubator to proactively onboard 100 social organizations onto the Free Basics platforms. This included large organizations like the World Food Programme or the UNHCR. But it also involved digitally oriented, Africa based civil society organizations like Code for Africa, Amandla Mobi, and Africa Check – and in a way, capturing actors that may have led the charge against Free Basics.

Other aspects of Facebook’s evolving strategy include:

- Reducing to none their public communication about Free Basics;

- investing in communities of developers and software engineers (particularly in Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa), who in India were at the forefront of the backlash;

- investing in other connectivity and infrastructural projects less opposable on net neutrality grounds, including the Express WI-FI initiative now available in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, South Africa, Senegal and Malawi; fiber optic cables in South Africa, Uganda and Nigeria; Internet Exchange Points (IXP), in partnership with the non-profit organization the Internet Society; and plans to build an undersea fiber optic cable surrounding the entire continent – and awkwardly code-named Simba.

- Greater interaction and partnerships with local civil society groups and digital rights communities to work on issues like misinformation, fact-checking, and online safety – and so again, here, building links with communities who may have led the challenge to Free Basics.

The second key phenomenon to consider is the broader political and regulatory landscape shaping the advocacy agenda of digital rights activism across the continent. As social media became increasingly involved in social protests and the ousting of authoritarian leaders, several governments have turned to radical strategies to crackdown on digital freedoms. These include internet shutdowns, social media taxes, cybersecurity laws violating privacy and attacking free speech, and the arrest of bloggers. For digital rights activists, government-led digital surveillance and repression have constituted particularly pressing threats. As a result, their advocacy has largely focused on state actors.

In addition, various forms of zero-rated projects already existed in several of these markets. As highlight by Hoskins (2019), zero-rating covers a range of practices of positive discrimination of web content by mobile ISPs that extend beyond ‘free’ services (like Free Basics and Wikipedia Zero) to include ‘differential pricing that is commonly used to sell app-specific bundles’. Among ICT policy experts on the continent, there has been a sense that banning zero-rating would negatively impact poorer users. Most notably, in 2016, ResearchICTAfrica -– an influential African ICT policy think tank – published a report arguing that regulators should not prohibit zero-rating when it enhances competition.

To summarize, my research highlights two interrelated processes behind Facebook’s ability to move forward with the project across Africa. The corporation retreated from grand public relations campaigns about its supposedly philanthropic intentions and opted for a greater engagement with civil society groups and less controversial infrastructural projects. For their part, digital rights activists found themselves facing threats from state actors that felt more pressing, thereby relegating issues of zero-rating regulation to the background of their advocacy agenda.

At a time of growing calls for imagining public interest digital ecosystem (for instance, Zuckerman, 2020), this story underscores investments made by tech corporations in new spaces, and which deserve critical attention from scholars, journalists and activists in the future.

On the one hand, it gives to see the ongoing and growing investments of Facebook in network infrastructures – a trend that other companies like Amazon and Google are also involved in. In addition to being monopolistic platforms in terms of content, one can envision here these foreign corporate actors also becoming almost like internet service providers – a form of vertical integration with far reaching consequences for network sovereignty and (un)democratic control of digital infrastructures.

On the other hand, it reveals growing and increasingly fraught interactions between civil society and tech corporations. Traditional civil society organizations find themselves increasingly reliant on digital corporate platforms and software – from activists using WhatsApp to the World Food Program and the UNHCR being partners to Free Basics. For their part, various digital rights activists in Africa are increasingly partnering with social media platforms to work on a range of issues – from misinformation and digital safety to election monitoring and fact-checking. All the while, they rely on philanthropic funding often linked to tech industry fortunes built on the global extraction of data. How this funding will affect the positioning of the digital rights community vis-à-vis social media platforms down the line, particularly regarding issues of social media regulation, remains to be seen.

***

This blog post is based on the following article: Nothias, T. (forthcoming 2020) “Access Granted: Facebook’s Free Basics in Africa.” Media, Culture & Society. The full paper is available open access here, and is part of a special issue on “Social Media and Democracy in Africa” edited by Bruce Mutsvairo and Helge Rønning.

Bio:

Toussaint Nothias is the Associate Director of Research at the Digital Civil Society Lab, Stanford University. His research explores journalism, civil society and digital technologies across several African contexts. He holds a PhD from the School of Media & Communication at the University of Leeds. You can find him on Twitter at @NothiasT.